MOGADISHU, Somalia – Years after a suicide bombing struck the venue, Hassan Barre approached the podium to showcase a distinctive art form: poetry.

In one of the globe’s most unstable regions, Somalis bear a responsibility toward their nation and fellow citizens, he declared during a performance highlighting civic duty.

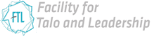

The 70-year-old Barre presented a grave appearance at the lectern. His words resonated throughout the sparsely attended auditorium of Mogadishu’s National Theater, where elderly poets in formal attire convene to recite verses and reminisce about better times.

These men, some with beards dyed henna and eyes clouded by glaucoma, symbolize a diminishing source of hope for a nation gradually deprived of its cultural heritage through prolonged warfare.

Oral poetry stands as perhaps Somalia’s most revered art form, recited in the most distant communities and even by extremists in remote areas.

Somalis are frequently characterized as “a nation of poets,” with their work typically celebrating pastoral prosperity and traditional gender roles in this predominantly Islamic nation. Certain poets, including Hadraawithe “Shakespeare of Somalia” who passed away in 2022 have gained international acclaim. “Hadraawi’s body of work encompasses a diverse collection, ranging from romantic ballads to mourning verses about conflict,” observed Harvard University’s Archive of World Music following his passing.

During Siad Barre’s rule, poets thrived despite his authoritarian governance, as he respected artistic intellectual contributions.

His 1991 ouster by clan militias triggered a civil war as warlords vied for powera chaos that ultimately facilitated the emergence of deadly militant groups.

Today, Somalia is renowned more for terrorist attacks than poetic expression. The violence has affected cultural institutions, which remain largely inactive as the unstable federal government allocates most of its budget to security.

The National Theater, adjacent to the National Museum, operates minimally.

Accessing the venue in a highly secured zone close to the presidential palace requires visitors arriving by vehicle to notify intelligence authorities beforehand, as security measures mandate not only the vehicle’s license plate but also its model and color.

The morning Barre recited his poem, a contingent of young Somalis rehearsed a folk dance highlighting traditional values such as diligent agricultural work.

Nearby, a gathering of poets, including a woman, conversed softly. Several informed The Associated Press they strive to maintain Somalia’s poetic heritage in spite of security apprehensions and financial constraints that restrict cultural programming.

Traditional poets continue to perform at community events such as weddings, while verses are broadcast daily on local radio stations.

Yet under Barre’s regime “we were regarded as royalty,” with some provided complimentary housing, stated poet Barre, no relation to the former President.

“The current administration offers little consideration to poets and performers. We anticipate treatment comparable to what we previously received.” Daud Aweis, Somalia’s Minister of Culture, affirmed that poets continue to fulfill “a crucial function in Somali society, acting as a fundamental support for cultural vibrancy, personal welfare and harmonious living.”

Though his department supplies restricted financing for cultural activities at the National Theater, “the objective is to broaden assistance over time,” he informed the AP.

Established in 1967, shortly after independence, the National Theater closed in 1991 following Barre’s removal.

It resumed operations in 2012 following African Union peacekeepers’ expulsion of Al-Shabaab militants from Mogadishu during an anti-terrorism initiative.

Several months afterward, though, a suicide bomber detonated herself at the theater during a prime minister’s address, resulting in the death of Somalia’s Olympic committee president and at least seven additional individuals.

The Prime Minister remained unharmed. Nevertheless, the poets convening at the National Theater persist in their efforts.

Assembling there cultivates communal spirit in a city fortified with sandbags and encircled by security posts.

Hirsi Dhuuh Mohamed, who leads the Somali Council of Poets, reported the organization comprises 400 members, numerous of whom reside abroad. He indicated conditions had advanced from “the darkest period” in the late 1990s, when Mogadishu was partitioned into territories as warlords contended for supremacy.

“What unites all Somali poets, whether in Eritrea, Somalia, or elsewhere, is our commitment to peace,” he remarked, noting they avoid direct political involvement.

Rather, he emphasized, the fundamental message of their creative output emphasizes security, effective administration and social cohesion.

Another poet, Maki Haji Banaadir, an ill-tempered individual with spectacles framed in gold, serves among those endeavoring to maintain the National Theater’s functionality as its deputy director.

In 2003, he and six fellow poets traversed Somalia to advocate for reconciliation. Such extensive travel is currently unfeasible.

The federal government exercises minimal control beyond Mogadishu, and at least two self-governing regions pursuing independence. Known commonly as Maki, he is a prominent cultural personality in Somalia. A decade prior, he wrote a song addressing the apparent worthlessness of the Somali shilling, which local markets no longer accept amid Somalia’s economic dollarization.

When questioned if he and his contemporaries were mentoring the subsequent generation of Somali poets, he expressed optimism: “We labor continuously.”