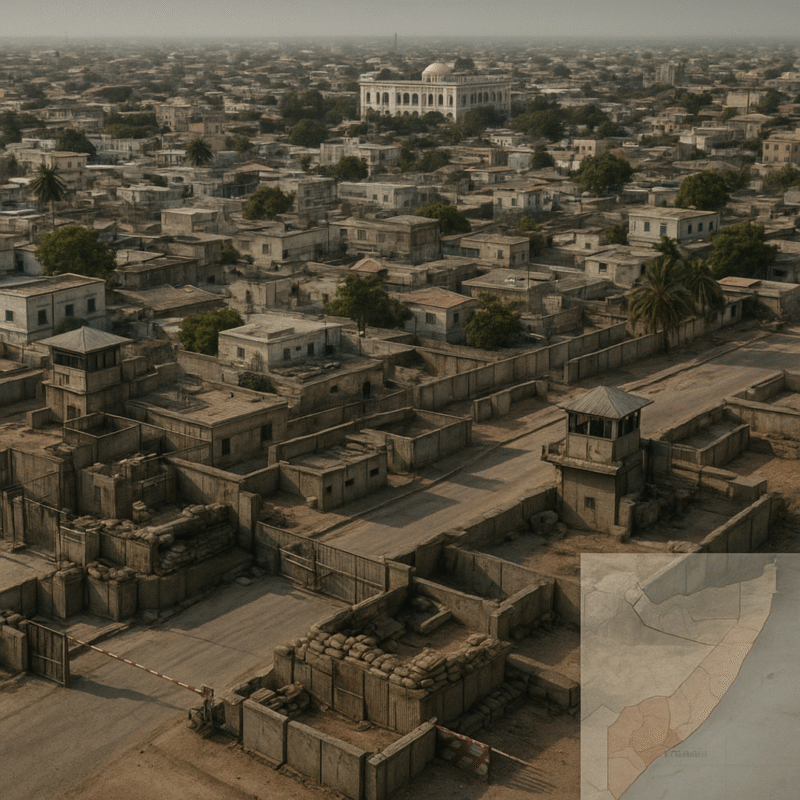

Mogadishu, Somalia – Recent reports have emerged regarding alleged Qatar-mediated discussions between Al-Shabaab and Somalia’s federal government. The key parties involved – Mogadishu, Al-Shabaab, and Doha – have neither confirmed nor denied these claims.

These allegations were amplified by journalist Abdalla Ahmed Mumin, founder of the Somali Journalists Syndicate (SJS), who subsequently reported that the purported discussions had fallen through.

Similar claims of “secret negotiations” have surfaced during previous political periods and were later dismissed as false or smear campaigns.

Although the validity of these recent assertions remains uncertain, analysts contend that meaningful negotiations between the two parties are unlikely under present political and military conditions.

This assessment is based on two decades of conflict, the stated positions of the actors involved, and the regional and international factors influencing Somalia’s war against Al-Shabaab.

A Conflict Characterized by Maximum Objectives

For almost two decades, Al-Shabaab has engaged in conflict with consecutive Somali administrations, resulting in significant casualties for both sides and the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians.

The organization’s origins can be traced to 2006, when it functioned as the armed branch of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU). The ICU maintained control over most of southern Somalia for a brief period before a substantial Ethiopian military intervention – supported by the United States – removed them from power.

Prior to that intervention, the ICU had insisted on two uncompromising demands:

These demands continue to form the core of Al-Shabaab’s ideology today and have repeatedly undermined efforts at reconciliation.

In 2008, moderate ICU leaders, headed by Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, signed a peace accord with the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) that facilitated Ethiopia’s withdrawal and established a power-sharing arrangement. Subsequently, Sharif was elected president.

Al-Shabaab rejected his administration, claiming it refused to govern according to Sharia law and remained reliant on foreign forces – specifically the African Union Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). Hostilities escalated, with militant forces at one point advancing to within meters of the presidential compound before being repelled by AU troops.

By late 2011, Al-Shabaab had retreated from Mogadishu and transitioned to guerrilla strategies aimed at stretching AU resources, creating donor fatigue, and positioning themselves for a prolonged effort to recapture national authority.

Is Al-Shabaab Willing to Negotiate?

In public statements, Al-Shabaab asserts it will not engage with Somalia’s federal government, which it characterizes as an “apostate” regime supported by Western powers. Senior leadership maintains that Mogadishu lacks the capacity to implement any agreement.

Certain analysts suggest that the organization might theoretically be open to negotiations – but only with the United States, which they perceive as the primary external influence in Somalia. Washington has consistently opposed direct contact with the group, which is classified as a foreign terrorist organization by the US, UN, and numerous other governments.

Although Al-Shabaab has conducted private negotiations for hostage releases with foreign countries, these arrangements have never evolved into substantive political discussions.

Is Mogadishu Prepared for Negotiations?

President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has stated on multiple occasions that his administration might eventually engage with Al-Shabaab, but only “from a position of strength”.

However, the administration has experienced substantial military reversals in recent months. A significant military offensive initiated in 2022 has largely stalled, with militant forces reclaiming territory and federal troops finding it difficult to maintain previous advances.

Politically, Mogadishu remains embroiled in conflicts with multiple federal member states – particularly Puntland and Jubbaland – regarding electoral arrangements and constitutional changes. The administration’s term is nearing conclusion, further limiting its influence.

Under these circumstances, Somali officials lack the necessary internal cohesion and military superiority needed for substantive negotiations.

Can Qatar Facilitate Discussions Without US Support?

Qatar has participated prominently in notable mediation efforts, ranging from Afghanistan to Gaza, but these initiatives received substantial US involvement.

Diplomats and regional observers suggest that Doha would be incapable of brokering a Somalia agreement without American backing, along with coordination with neighboring countries like Kenya and Ethiopia – both of which perceive Al-Shabaab as an immediate security concern and are highly suspicious of any process that might enhance the group’s political standing.

Assertions that Qatar is operating independently are generally considered by specialists to be unrealistic.

Barriers to Any Settlement Through Negotiation

Numerous significant obstacles would complicate even initial discussions:

1. Fundamental political divisions within Somalia

Federal member states, particularly Puntland, Jubaland, and the self-declared republic of Somaliland, would firmly resist any negotiations exclusively directed by Mogadishu. They frequently accuse the central government of accommodating or supporting militant groups – allegations that federal authorities deny.

2. Robust opposition from regional powers

Both Kenya and Ethiopia object to any resolution that might permit an Islamic administration to govern Mogadishu. These nations also worry about Al-Shabaab’s territorial ambitions extending across their borders.

3. Al-Shabaab’s fundamental demands

The organization continues to insist on:

International partners, especially the United States, view a complete military withdrawal as unacceptable because of security concerns. These stances create an immediate diplomatic impasse.

4. Al-Shabaab’s alliance with Al-Qaeda

Although analysts acknowledge that the organization could theoretically disavow the global network, severing formal connections would not resolve its ideological objectives or territorial aspirations. Most experts concur that Al-Shabaab seeks an “Afghanistan-style” triumph rather than power-sharing arrangements.

Lessons from Afghanistan and Syria Are Not Transferable to Somalia

Al-Shabaab has carefully monitored the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan and the development of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in Syria. However, the Somali situation differs markedly.

Afghanistan’s Taliban assumed authority following a US-negotiated withdrawal and the disintegration of Afghan government forces. No regional government openly resisted the Taliban’s seizure of power.

HTS in northwest Syria acquired influence partially through discreet interactions with foreign powers and a readiness to compromise on ideological principles.

In contrast, in Somalia, no neighboring country supports an Al-Shabaab takeover, and Ethiopia and Kenya maintain substantial military deployments in regions adjacent to their borders.

A Conflict Destined to Persist

During recent months, Al-Shabaab has enhanced its activities in the areas surrounding Mogadishu, establishing temporary checkpoints on major access routes. These actions demonstrate both the organization’s confidence and the government’s strained security infrastructure.

However, despite periodic speculation about a negotiated resolution to the conflict, both parties appear committed to a military strategy.

For Al-Shabaab, negotiations risk internal fragmentation without achieving its ultimate aim: a complete Islamic emirate.

For the government, discussions – particularly amidst political instability – could undermine its legitimacy and provoke criticism from competing states and domestic opponents.

Currently, Somalia’s prolonged conflict appears destined to continue, with neither side positioned to pursue, embrace, or execute a political resolution.